Italian Cinema – Between Artistic Brilliance and Popular Passion

The Pioneers (1895 – 1919)

Italian cinema was born at the end of the 19th century and established itself as a European powerhouse by the 1910s. Giovanni Pastrone made history with Cabiria (1914), a monumental historical epic that revolutionized the use of camera movement and grandiose sets. Films from this period favored meticulous reconstructions, spectacular staging, and subjects drawn from antiquity or patriotic themes. Italy distinguished itself by its ability to produce great historical films that would inspire Hollywood, but World War I and foreign competition slowed its momentum.

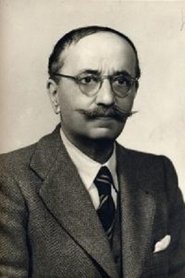

The Pioneers

The 1920s–1930s: Between Decline and Propaganda

In the 1920s, Italian film production declined in the face of Hollywood and the economic crisis. Under the fascist regime, cinema became a political tool, but also a space for technical experimentation. The creation of the Cinecittà studios in 1937 launched a new industrial era. Screens filled with light comedies, melodramas, and historical films, carried by popular actors. This period set the stage for the major transformation to come.

The 1920s–1930s

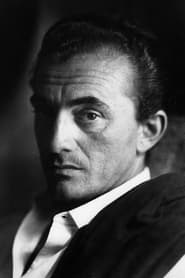

Neorealism (1945 – early 1950s)

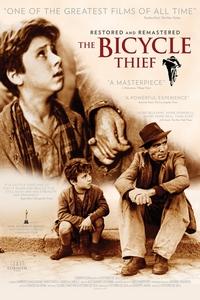

After World War II, Italy invented neorealism, a movement that filmed real life, the streets, ordinary faces, and everyday hardships. Roberto Rossellini (Rome, Open City, 1945), Vittorio De Sica (Bicycle Thieves, 1948), and Luchino Visconti (La Terra Trema, 1948) shook the film world with their sincerity and humanity.

Neorealism became a model for many countries, leaving a lasting influence on cinematic language.

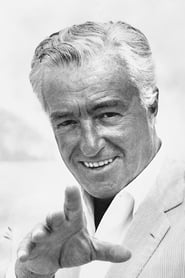

Neorealism

The 1950s–1960s: The Golden Age and Popular Genres

The 1950s and 1960s saw the blossoming of a golden age. Federico Fellini blended dream and reality (La Dolce Vita, 1960; 8½, 1963), Michelangelo Antonioni analyzed modern alienation (L’Avventura, 1960), and Sergio Leone invented the spaghetti western (For a Few Dollars More, Once Upon a Time in the West).

At the same time, commedia all’italiana, led by Dino Risi, Mario Monicelli, and Pietro Germi, humorously and ironically depicted social changes. Peplum (sword-and-sandal epics) and gothic horror films completed a panorama of exceptional richness.

The 1950s–1960s

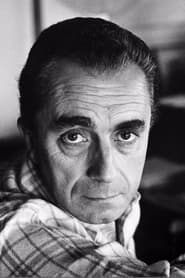

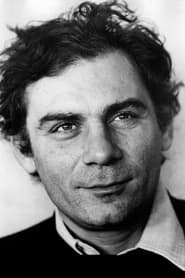

The 1970s–1980s: Politics, Giallo, and International Epics

In the 1970s, Italian cinema became politicized with films engaged in history and social struggles. The giallo (horror thriller) reached its peak thanks to Dario Argento (Deep Red, 1975). Bernardo Bertolucci created international epics (Last Tango in Paris, 1972; The Last Emperor, 1987).

Popular cinema remained strong, but filmmakers explored more radical and diverse forms.

The 1970s–1980s

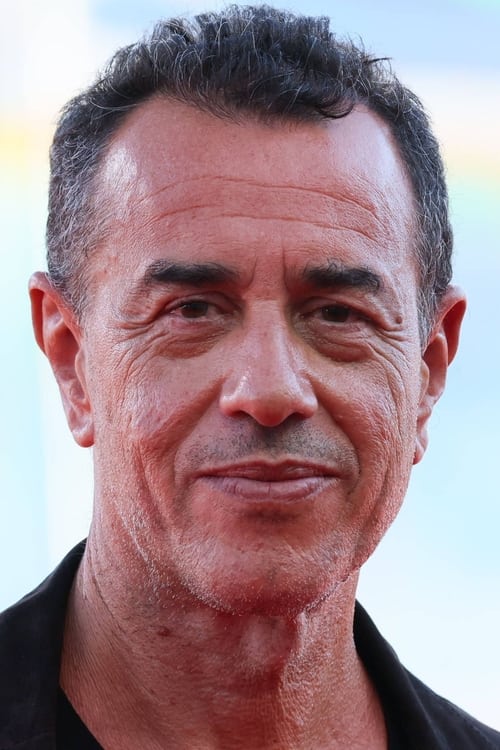

The 1990s–2000s: Internationalization and Memory

Italian cinema alternated between global successes and a strong attachment to local context. Giuseppe Tornatore paid tribute to cinema with Cinema Paradiso (1988) and continued with Malèna (2000). Nanni Moretti established a personal tone between comedy and introspection (The Son’s Room, Palme d’Or 2001).

Co-productions intensified, and Italian directors became part of a more integrated European cinema.

The 1990s–2000s

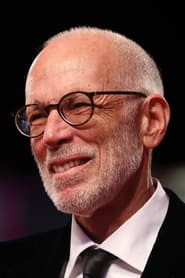

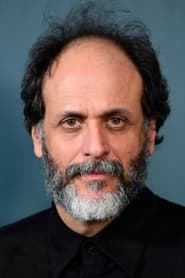

Since 2010: Aestheticism and Contemporary Boldness

Contemporary Italian cinema remains true to its dual heritage: refined auteur cinema and a vibrant popular tradition. Paolo Sorrentino has won over critics (The Great Beauty, Oscar 2014), Matteo Garrone impressed with Gomorrah (2008) and Pinocchio (2019). Young filmmakers explore social themes, identity, and contemporary history, while participating in major international festivals.